This article is the result of reader comments following my past article, “12 Major Battles of ,the Vietnam War.” https://cherrieswriter.wordpress.com/2017/01/03/12-major-battles-of-the-vietnam-war/

There were many comments split between my Vietnam Facebook groups and following the posted article that challenged the word “Major” insisting that anytime participants were fired upon and placed in harms’ way, then in their minds, it wasn’t just a skirmish, ambush or sniper – to them, it was a major experience. Personally, I never knew the names of any of the Operations or battles that I had participated in. All I know is when the shooting started, it was a battle; doesn’t matter if it lasted five minutes or sporadically for a month.

I’ve listed those battles mentioned from your comments along with notes and pictures about each one. Beware: this article is extremely long (31,000 words and 136 pages) – the equivalent of a short novel. I’ve added as much detail as possible to see the “big picture” and hope it meets with your approval. I also hope that readers find this article educational and learn more about the Vietnam War from the information provided. Kudos to anyone able to read the entire article in one setting!

Note that these engagements are neither listed chronologically nor are they in order of importance. They are only suggestions deemed important to mention from my readers. They are also posted in the order that I recorded them from your notes:

Operation Prairie I-IV

Battle of Con Tien

Battle of Dong Ha

Operation Allen Brook

Operation Hump

Battle of An Loc

Operation Lam Son 719

Battle of Quang Tri Province

Battle of Ben Het Special Forces Camp

Battle of Binh Ghia

The Hill Fights

Battle of Trang Bang

Battle of Tam Quang

Operation Cedar Falls

Operation Dewey Canyon

The Cambodian Campaign

Attack on FSB Jay

Attack on FSB Illingworth

Battle of Ap Gu

Operation Prairie I

This was a U.S. military operation in northern South Vietnam that sought to eliminate North Vietnamese Army (NVA) forces south of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ).Over the course of late 1965 and early 1966 the Viet Cong (VC) and North Vietnamese Army (NVA) intensified its military threat along the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). The tactical goal of these incursions across the 17th Parallel sought to draw United States Military forces away from populated cities and towns, a similar strategy would be employed during the final months of 1967 in order to maximize the impact of the upcoming Tet Offensive. In response, the Marines elected to construct and reinforce a string of firebases due south of the DMZ including installments at Con Thien, Gio Linh, Camp Carroll, and Dong Ha. To support the defense of the DMZ area, Marines were often relocated from the southern regions of I Corps. In addition to these firebases, U.S. forces also established an interconnected sequence of electronic sensors and other detection devices called the McNamara Line.

Map of the demilitarized zone and northern Quang Tri Province during the Vietnam War

The original actions in defense of the Vietnamese DMZ, officially designated as Operation Hastings, began on 15 July 1966. Operation Hastings was a strategic success for American and South Vietnamese troops as the estimated enemy casualties reached upwards of 800 enemy soldiers. The operation, however, was only scheduled to last slightly longer than three weeks reaching its conclusion on 3 August 1966.

Due to the initial, albeit brief, successes of Operation Hastings the United States elected to essentially renew the mission and rename it, Operation Prairie. Operation Prairie would cover the exact same areas along the DMZ that Operation Hastings had, as well as had the same mission. The formal objective of Prairie was to search the areas south of DMZ for NVA troops and eliminate them. Another purpose of Operation Prairie aimed to determine the extent of NVA and VC infiltration of northern I Corps, the area of South Vietnam stretching from the northern edge of the Central Highlands to the DMZ.

.

Over the course of the next few hours Major Vincil W. Hazelbaker landed his UH-1E helicopter under withering enemy fire to resupply the Marines. Hazelbaker then departed, reloaded his helicopter at Dong Ha Airfield, and bravely returned. After several unsuccessful landing attempts Hazelbaker finally safely landed on the ground, resupplied the troops a second time, however during the unloading of ammunition an enemy rocket impacted the rotor mast, crippling the aircraft. Hazelbaker then assumed command, as Captain Lee had been injured by a fragmentation grenade, and directed a napalm strike on the enemy position at dawn on 9 August 1966. Reinforcements finally arrived later that morning, secured the area, and aided in the evacuation of the remaining Marines in the afternoon. In total Team Groucho Marx and their reinforcements suffered thirty-two casualties, with five men killed, while they inflicted at least thirty-seven enemy KIAs (a support team later noted other bloodstains and drag marks indicating a much larger higher number of casualties). For the valiant actions occurring during the two-day fight, Captain Howard V. Lee earned the Medal of Honor and Major Vincil W. Hazelbaker was presented the Navy Cross.

On 15 September 1966, an additional 1,500 Marines landed from 7th Fleet ships off Quang Tri province to support two companies of the 4th Marine Regiment who were pinned down by a large force of NVA troops. The outnumbered American forces were unable to break out until 18 September 1966. Operation Prairie concluded on 31 January 1967 with a total of 1,397 known enemy casualties.

Operation Prairie II

The allied forces renewed the operation several times during the first half of 1967 beginning with Operation Prairie II, which spanned from 1 February to 18 March and accounted for a total of 693 enemy casualties.

Operation Prairie III

Operation Prairie III began just two days after the conclusion of Prairie II on 20 March and lasted until 19 April 1967 with an enemy casualties estimated at 250 soldiers.

Operation Prairie IV

Operation Prairie IV ran from 20 April to 17 May 1967 and featured heavy fighting east of Khe Sanh along the southern banks of the Ben Hai River, including five battalions of the 1st Division of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) and three battalions of Marines and the Special Landing Force. By the time Prairie IV wrapped up actions, a total of 164 American troops had been killed with approximately 999 wounded, while the NVA suffered 505 deaths with an unknown number of wounded.

Operation Prairie was undoubtedly a huge success for the American and South Vietnamese forces, however, its primary triumphs were overshadowed in the months and years that followed. The allied forces accomplished exactly what had been outlined in Prairie’s objectives: prevent enemy infiltration across the DMZ and Ben Hai River and determine the extent of their infiltration. Nevertheless, the NVA units merely fled over the DMZ to North Vietnam in order to regroup, re-equip, and then reenter South Vietnam later in 1967. One of the other purposes of Operation Prairie was to reduce the large investment of manpower that the U.S. forces had committed to protect the DMZ. Instead, the NVA strategy tied down a major portion of the Marine force in I Corps along the vast, barren tracts of land south of the DMZ, leaving population centers undermanned and under protected.

Battle of Con Tien

This battle occurred during Operation Prairie I and is included in the information above. Therefore, I’ve added a 25 minute documentary to tell this story.

Battle at Dong Ha

In the spring of 1968, after the Tet Offensive and before the opening of the Paris peace talks, the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and Vietcong made a determined effort to improve their bargaining position. They conducted 119 attacks on provincial and district capitals, military installations, and major cities in South Vietnam. The United States Marines maintained a supply base at Dong Ha in I Corps.

It was in the northeastern area of Quang Tri Province. Late in April and early in May, the NVA 320th Division, with 8,000 troops, attacked Dong Ha and fought a rigorous battle against an allied force of 5,000 marines and South Vietnamese soldiers. The North Vietnamese failed to destroy the supply base and had to retreat back across the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), leaving behind 856 dead. Sixty-eight Americans died in the fighting.

Operation Allen Brook

This was a US Marine Corps operation that took place south of Danang, lasting from 4 May to 24 August 1968.

Go Noi Island was located approximately 25 km south of Danang to the west of Highway 1, together with the area directly north of the island, nicknamed Dodge City by the Marines due to frequent ambushes and firefights there, it was a Vietcong and People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) stronghold and base area. While the island was relatively flat, the small hamlets on the island were linked by hedgerows and concealed paths providing a strong defensive network. Go Noi was the base for the Vietcong’s Group 44 headquarters for Quảng Nam Province, the R-20 and V-25 Battalions and the T-3 Sapper Battalion and, it was believed, elements of the PAVN 2nd Division.

On the morning of 4 May 1968 two Companies of the 2nd Battalion 7th Marines supported by tanks crossed the Liberty Bridge onto the island meeting only light resistance for the first few days. On 7 May Company A 1st Battalion 7th Marines relieved one Company from 2/7 Marines and Company K 3/7 Marines was added to the operation. By 8 May the Marines had lost 9 killed and 57 wounded and the Vietcong 88 killed. On the evening of 9 May the Marines encountered heavy resistance at the hamlet of Xuan Dai, after calling in air strikes the Marines overran the hamlet resulting in 80 PAVN killed.

On 13 May Company I 3rd Battalion 27th Marines was deployed to the Que Son mountains southwest of Go Noi moving east onto the island and the Marines on the island began sweeping west linking up at the Liberty Bridge on 15 May. Company E 2/7 Marines and the command group were airlifted out of the area on the evening of 15 May.

The Marines then began a deception plan crossing the Liberty Bridge as if the operation had concluded and then crossing back onto the island on the early morning of 16 May. At 09:00 on 16 May 3/7 Marines encountered a PAVN Battalion at the hamlet of Phu Dong, the Marines were unable to outflank the PAVN and called in air and artillery support as the battle continued all day. By nightfall the PAVN abandoned their positions leaving more than 130 dead while Marine losses were 25 dead and 38 wounded. The hamlet was found to contain a PAVN Regimental headquarters and vast quantities of supplies.

On the morning of 17 May 3/7 Marines moved out of Phu Dong patrolling southeast. Company I 3/27 Marines was leading the column when it was ambushed by a strongly entrenched PAVN force near the hamlet of Le Nam. The other Marine Companies attempted to assist Company I but the PAVN defenses proved too strong and artillery support was the only way to relieve the pressure on Company I. It was decided that Companies K and L 3/27 Marines would air assault into the area and the first helicopters landed at 15:00 and Company K broke through to relieve Company I at 19:30 while the PAVN withdrew. Marine losses were 39 dead and 105 wounded while PAVN losses were 81 killed. PFC Robert C. Burke a machine-gunner in Company I would be posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions during the battle.

On 18 May 3rd Battalion 5th Marines replaced 3/7 Marines and operational control passed to 3/27 Marines. At 09:30 the Marines began taking sniper fire from the hamlet of Le Bac (2). Companies K and L were sent to clear out the snipers but were quickly pinned down by another well-prepared PAVN ambush. Airstrikes and artillery fire was called in but due to the proximity of the opposing forces were of limited effect. At 15:00 Company M 3/27 Marines arrived by helicopter to replace Company L and cover the retreat of Company K and air and artillery strikes were directed against Le Bac (2). Marine losses were 15 killed, 35 wounded and over 90 cases of heat exhaustion while PAVN losses were 20 killed.

For the next 6 days the Marines continued patrolling, suffering frequent ambushes despite strong preparatory fires. The Marines altered their tactics so that when the enemy was encountered they would hold their positions or pull back to allow air and artillery to deal with the entrenched forces. From 24–27 May a sustained fight took place at the hamlet of Le Bac (1), only ending when torrential rain made further fighting impossible. By the end of May total casualties for the battle were 138 Marines killed and 686 wounded while PAVN/Vietcong losses exceeded 600 killed.

On 26 May the 1st Battalion 26th Marines reinforced the operation, while on the 28th 3/27 Marines was relieved by 1st Battalion 27th Marines and 3/5 Marines was returned to the Division reserve. During early June the 1/26 and 1/27 Marines carried out ongoing search and clear operations on the island with regular ambushes by small PAVN/Vietcong forces.

On 5 June as the Marine Battalions moved west along the island they were ambushed by a PAVN force at the hamlet of Cu Ban (3), due the proximity of the enemy forces supporting fire was ineffective and a confused close-quarters battle raged throughout the day until tanks allowed the Marines to overrun the enemy positions. Marines losses were 7 killed and 55 wounded while PAVN losses were 30 killed.

On 6 June 1/26 Marines was withdrawn from the operation and elements of the 1st Engineer Battalion arrived with orders to destroy the fortifications on Go Noi with 1/27 Marines providing security. On the early morning of 15 June a PAVN force attacked Company B 1/17 Marines’ night defensive position, the attack was defeated with 21 PAVN killed with no Marine losses.

On 19 June Companies B and D were ambushed by the PAVN at the hamlet of Bac Dong Ban, the fight lasted 9 hours before the Marines were able to overrun the PAVN bunkers. Marine losses were 6 killed and 19 wounded while the PAVN lost 17 killed.

On 23 June 2nd Battalion 27th Marines relieved 1/27 Marines on Go Noi. 2/27 Marines stayed on Go Noi until 16 July when it was relieved by 3/27 Marines. Marine losses during this period were 4 Marines killed and 177 wounded for 144 PAVN/Vietcong killed.

On 31 July, BLT 2/7 Marines which had just completed Operation Swift Play in the Da The mountains 6 km south of Go Noi arrived on the island and relieved 3/27 Marines.

Land clearing operations on Go Noi continued into August by which time much of the island had been completely leveled and seeded with herbicides. As enemy activity had been reduced to a minimal level it was decided to close the operation. While much of their infrastructure had been destroyed the PAVN/Vietcong continued to resist until the last as the Marines and Engineers withdrew across the Liberty Bridge harassed by sniper fire.

Operation Allen Brook concluded on 24 August, the Marines had suffered 172 dead and 1124 wounded and the PAVN/Vietcong 917 killed and 11 captured.

Operation Hump

This was a search and destroy operation initiated on 8 November 1965 by the 173rd Airborne Brigade, in an area about 17.5 miles (28.2 km) north of Bien Hoa. The 1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment deployed south of the Dong Nai River while the 1st Battalion, 503rd Infantry, conducted a helicopter assault on an LZ northwest of the Dong Nai and Song Be Rivers. The objective was to drive out Vietcong fighters who had taken position in several key hills. Little contact was made through 7 November, when B and C Companies settled into a night defensive position southeast of Hill 65, in triple-canopy jungle.

At about 06:00 on 8 November C Company began a move northwest toward Hill 65, while B Company moved northeast toward Hill 78. Shortly before 08:00, C Company was engaged by a sizeable enemy force well dug into the southern face of Hill 65, armed with machine guns and shotguns. At 08:45, B Company was directed to wheel in place and proceed toward Hill 65 with the intention of relieving C Company, often relying on fixed bayonets to repel daring close range attacks by small bands of masked Vietcong fighters.

B Company reached the foot of Hill 65 at about 09:30 and moved up the hill. It became obvious that there was a large enemy force in place on the hill, C Company was suffering heavy casualties, and by chance, B Company was forcing the enemy’s right flank.

Under pressure from B Company’s flanking attack the enemy force—most of Vietcong regiment—moved to the northwest, whereupon the B Company commander called in air and incendiary artillery fire on the retreating rebels. The shells scorched the foliage and caught many rebel fighters ablaze, exploding their ammunition and grenades they carried. B Company halted in place in an effort to locate and consolidate with C Company’s platoons and managed to establish a coherent defensive line running around the hilltop from southeast to northwest, but with little cover on the southern side.

Meanwhile, the Vietcong commander realized that his best chance was to close with the US forces so that the 173rd’s air and artillery fire could not be effectively employed. Vietcong troops attempted to out-flank the US position atop the hill from both the east and the southwest, moving his troops closer to the Americans. The result was shoulder-to-shoulder attacks up the hillside, hand-to-hand fighting, and isolation of parts of B and C Companies; the Americans held against two such attacks. Although the fighting continued after the second massed attack, it reduced in intensity as the Vietcong troops again attempted to disengage and withdraw, scattering into the jungle to throw off the trail of pursuing US snipers. By late afternoon it seemed that contact had been broken, allowing the two companies to prepare a night defensive position and collect their dead and wounded in the center of the position. Although a few of the most seriously wounded were extracted by USAF helicopters using Stokes litters, the triple-canopy jungle prevented the majority from being evacuated until the morning of 9 November.

The result of the battle was heavy losses on both sides—49 Paratroopers dead, many wounded, and 403 dead Vietcong troops as an estimate by the US troops.

Operation Hump is memorialized in a song by Big and Rich named 8th of November. The introduction, as read by Kris Kristofferson, is:

Battle of An Loc

The Battle of An Lộc was a major battle of the Vietnam War that lasted for 66 days and culminated in a decisive victory for South Vietnam. In many ways, the struggle for An Lộc in 1972 was an important battle of the war, as South Vietnamese forces halted the North Vietnamese advance towards Saigon.

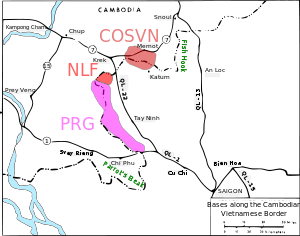

On the evening of April 7, elements of the PAVN 9th Division overran Quần Lợi Base Camp. Its defenders, the 7th Regiment of the 5th Division, were ordered to destroy their heavy equipment (including a combined 105mm and 155mm artillery battery) and fall back to An Lộc. Once captured, the PAVN used Quần Lợi as a staging base for units coming in from Cambodia to join the siege of An Lộc. Key members of COSVN were based there to oversee the battle.

On April 8, the small town of Lộc Ninh was overrun and about half of the defenders escaped to An Lộc.

The ARVN defenders (8,000 strong) did have one card to play throughout the battle, the immense power of U.S. air support. The use of B-52 Stratofortress bombers (capable of carrying 108 MK82 (500 pound) bombs on one run) in a close support tactical role, as well as AC-119 Stinger and AC-130E Spectre gunships, fixed-wing cargo aircraft of varying sizes, AH-1 Cobra attack helicopters and Vietnamese Air Force (VNAF) A-37s. These methods worked to blunt the PAVN offensive. At this stage in the war, the PAVN often attacked with PT-76 amphibious and T-54 medium tanks spearheading the advance, usually preceded by a massive artillery barrage. These tactics reflected Soviet doctrine, as the PAVN had been supplied with Soviet and Chinese Communist equipment, including jets, artillery, and surface to air missiles since the beginning of the war. The battle eventually stagnated and became a periodic trade of artillery barrages. This was most probably a result of casualties sustained in the frustrated attacks on heavily entrenched enemy positions in control of a withering array of supporting firepower.

The first attack on the city occurred on April 13 and was preceded by a powerful artillery barrage. The PAVN captured several hills to the north and penetrated the northern portion of the city held by the 8th Regiment and 3rd Ranger Group. ARVN soldiers were not accustomed to dealing with tanks, but early success with the M72 LAW, including efforts by teenaged members of the PSDF went a long way to helping the overall effort. The 5th Division commander, General Hung, later ordered tank-destroying teams be formed by each battalion, which included PSDF members who knew the local terrain and could help identify strategic locations to ambush tanks. They took advantage of the fact that the PAVN forces, who were not used to working with tanks, often let the tanks get separated from their infantry by driving through ARVN defensive positions. At that point, all alone inside ARVN lines, they were vulnerable to being singled out by tank-destroying teams.

April 15 saw the second attack on the city. The PAVN were concerned that because the ARVN 1st Airborne Brigade had air-assaulted into positions west of the city, that they were now coming to reinforce the defenders. Again the PAVN preceded their attack with an artillery barrage followed by a tank-infantry attack. Like before, their tanks became separated from their infantry and fell prey to ARVN anti-tank weapons. PAVN infantry followed behind the tank deployment, assaulted the ARVN defensive positions, and pushed farther into the city. B-52 strikes helped break up some PAVN units assembling for the attack. This engagement lasted until tapering off on the afternoon of April 16.

Unable to take the city, the PAVN kept it under constant artillery fire. They also moved in more anti-aircraft guns to prevent aerial resupply. Heavy anti-aircraft fire kept VNAF helicopters from getting into the city after April 12. In response, fixed wing VNAF aircraft (C-123’s and C-119’s) made attempts, but after suffering loses, the U.S. Air Force took over on April 19. The US used C-130’s to parachute in supplies, but many missed the defenders and several aircraft were shot down or damaged. Low altitude drops during day and night did not do the job, so by May 2, the USAF began using High Altitude Low Opening (HALO) techniques. With far greater success, this method of resupply was utilized until June 25, when the siege was lifted and aircraft could land at An Lộc. Over the entire course of the resupply effort, the garrison recovered several thousand tons of supplies—the only supplies it received during the siege.

On May 11, 1972, the PAVN launched a massive all-out infantry and armor (T-54 medium tanks) assault on An Lộc. The attack was carried out by units of the 5th and 9th PAVN divisions. This attack was repulsed by a combination of U.S. airpower and the determined stand of ARVN soldiers on the ground. Almost every B-52 in Southeast Asia was called in to strike the massing enemy tanks and infantry. The commander of the defending forces had placed a grid around the town creating many “boxes”, each measuring 1 km by 3 km in size, which were given a number and could be called by ground forces at any time. The B-52 cells (groups of 3 aircraft) were guided onto these boxes by ground-based radar. During May 11 and 12, the U.S. Air Force managed an “Arc Light” mission every 55 minutes for 30 hours straight—using 170 B-52’s and smashing whole regiments of PAVN in the process. Despite this air support, the PAVN made gains, and were within a few hundred meters of the ARVN 5th Division command post. ARVN counter-attacks were able to stabilize the situation. By the night of May 11, the PAVN consolidated their gains. On May 12, they launched new attacks in an effort to take the city, but again failed. The PAVN launched one more attack on May 19 in honor of Ho Chi Minh’s birthday. The defenders were not surprised, and the attack was broken up by U.S. air support and an ambush by the ARVN paratroopers.

After the attacks of May 11 and 12, the PAVN directed its main efforts to cut off any more relief columns. However, by the 9th of June this proved ineffective, and the defenders were able to receive the injection of manpower and supplies needed to sweep the surrounding area of PAVN. By June 18, 1972, the battle had been declared over.

The victory, however, was not complete, QL-13 still was not open. The ARVN 18th Division was moved in to replace the exhausted 5th Division. The 18th Division would spread out from An Lộc and push the PAVN back, increasing stability in the area.

On August 8, the 18th Division launched an assault to retake Quần Lợi, but was stopped by the PAVN in the base’s reinforced concrete bunkers. A second attack was launched on August 9 with limited gains. Attacks on the base continued for 2 weeks; eventually one-third of the base was captured. Finally, the ARVN attacked the PAVN-occupied bunkers with TOW missiles and M-202 rockets, breaking the PAVN defense and forcing the remaining defenders to flee the base.

The fighting at An Lộc demonstrated the continued ARVN dependence on U.S. air power and U.S. advisors. For the PAVN, it demonstrated their logistical constraints; following each attack, resupply times caused lengthy delays in their ability to properly defend their position.

Operation Lam Son 719

Despite equivocal results in Cambodia, less than a year later the Americans pressed the South Vietnamese to launch a second cross-border operation, this time into Laos. Although the United States would provide air, artillery, and logistical support, Army advisers would not accompany South Vietnamese forces. The Americans’ enthusiasm for the operation exceeded that of their allies. Anticipating high casualties, South Vietnam’s leaders were reluctant to involve their army once more in extended operations outside their country.

The Ho Chi Minh Trail was an ever-changing network of paths and roads. For North Vietnam, keeping the Ho Chi Minh Trail open was a top priority. American intelligence had detected a North Vietnamese buildup in the vicinity of Tchepone, Laos, a logistical center on the Ho Chi Minh Trail approximately twenty-five miles west of the South Vietnamese border. The Military Assistance Command regarded the buildup as a prelude to a North Vietnamese spring offensive in the northern provinces. Like the Cambodian incursion, the Laotian invasion was justified as benefiting Vietnamization, but with the added bonuses of spoiling a prospective offensive and cutting off the Ho Chi Minh Trail. This would be the last chance for the South Vietnamese to cut the Ho Chi Minh Trail while American forces were available to provide support.

Phase I, designated DEWEY CANYON II, began at 0001 local time on 30 January, as US troops maneuvered to secure western Quang Tri province. An assault airstrip became operational at Khe Sanh by 3 February; Route 9 was repaired and cleared to the Laotian border by 5 February. Behind this cover, the better part of two South Vietnamese divisions massed at Khe Sanh in preparation for the cross border attack.

Because of security leaks, the North Vietnamese were not deceived. Within a week South Vietnamese forces numbering about 17,000 became bogged down by heavy enemy resistance, bad weather, and poor attack management. The ARVN had run into a superior North Vietnamese force fighting on a battlefield that the enemy had carefully prepared. In midsummer 1970, the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) General Staff began drawing up combat plans, deploying forces, and directing preparation of the battlefield. By 8 February 1971, when the ARVN crossed the Laotian border, the North Vietnamese, by their own account, had massed some 60,000 troops in the Route 9-Southern Laos front. They included five main force divisions, two separate regiments, eight artillery regiments, three engineer regiments, three tank battalions, six anti-aircraft regiments, and eight sapper battalions, plus logistic and transportation units-according to North Vietnamese historians “our army’s greatest concentration of combined-arms forces . . . up to that point.”

Aided by heavy U.S. air strikes, including B-52s, and plenty of artillery and helicopter gunship support, the South Vietnamese inched forward and after a bloody, month-long delay, air-assaulted on March 6 into the heavily bombed town of Tchepone. This was the last bit of good news from the front. This was the RVNAF’s last chance to make a dramatic impression upon the North Vietnamese. The North Vietnamese by now had massed five divisions with perhaps 45,000 troops-more than twice the ARVN force in Laos-for counterattacks. The North Vietnamese counterattacked with Soviet- built tanks, heavy artillery, and infantry. They struck the rear of the South Vietnamese forces strung out on Highway 9, blocking their main avenue of withdrawal. Enemy forces also overwhelmed several South Vietnamese firebases, depriving South Vietnamese units of desperately needed flank protection. The South Vietnamese also lacked enough antitank weapons to counter the North Vietnamese armor that appeared on the Laotian jungle trails and were inexperienced in the use of those they had. U.S. Army helicopter pilots flying gunship and resupply missions and trying to rescue South Vietnamese soldiers from their besieged hilltop firebases encountered intense antiaircraft fire.

On March 16, ten days after Tchepone was taken, President Thieu issued the order to pull out, turning aside General Abrams’ plea for an expansion of the offensive to do serious damage to the trail.

The ARVN withdrawal, conducted mainly along Route 9, ran from 17 until 24 March. A North Vietnamese ambush on 19 March littered the road with wrecked vehicles. Artillery pieces were abandoned, and a good many men had to make their way on foot to landing zones for evacuation. American media carried pictures of ARVN soldiers clinging to the skids of US helicopters.

The South Vietnamese lost nearly 1,600 men. The U.S. Army’s lost 215 men killed, 1,149 wounded, and 38 missing. The Army also lost 108 helicopters, the highest number in any one operation of the war. Supporters of helicopter warfare pointed to heavy enemy casualties and argued that equipment losses were reasonable, given the large number of helicopters and helicopter sorties (more than 160,000) that supported LAM SON 719. The battle nevertheless raised disturbing questions among Army officials about the vulnerability of helicopters in mid- or high-intensity conflict to any significant antiaircraft capability.

Watch a short 5-minute video from an American pilot who participated in the operation. Afterward, click on the back arrow key to return to this article:

Battle of Quang Tri Province

The Battle for Quang Tri occurred in and around Quang Tri City (Quang Tri Province), the northernmost provincial capital of Republic of South Vietnam during the Tet Offensive when the Vietcong and People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) attacked Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) and American forces across major cities and towns in South Vietnam in an attempt to force the Saigon government to collapse. This included several attacks across northern I Corps, most importantly at Hue, Da Nang and Quang Tri City. After being put on the defensive in the city of Quang Tri, the anti-communist forces regrouped and forced the communists out of the town after a day of fighting.

In 1968, Quang Tri City was a small market town and the capital of Quang Tri Province, the northernmost province of South Vietnam, bordering North Vietnam to the north, and Laos to the west. Like the old imperial capital at Hue, Quang Tri City is located on Route 1. It is about 10 kilometers (6.2 mi) inland from the South China Sea along the eastern bank of the Thach Han River, 25 kilometers (16 mi) south of the former Demilitarized Zone. Because Quang Tri City was an important symbol of South Vietnamese government authority and was arguably the most vulnerable provincial capital in South Vietnam, it was a prime target of the North Vietnamese during the 1968 Tet Offensive. The North Vietnamese had attacked and briefly overrun and occupied the city ten months earlier, on April 6, 1967, in a large scale coordinated attack by a reinforced PAVN regiment, inflicting significant casualties on Allied Forces before the attack was defeated. They freed 220 Communist prisoners from a city prison, and caused widespread destruction at ARVN facilities in and around the city and in adjacent districts. The permanent loss of the city to the Communists would be a political embarrassment and weaken the government’s legitimacy, and would allow the establishment of a Communist administrative center in the South. The question was not whether the Communists would attack Quang Tri City again, but when.

Particularly given their failure to hold Quang Tri City after overrunning and briefly occupying it in April 1967 despite committing a large force of about 2,500 men, the Communists became more aware of the difficulties of attacking and capturing the city. In the weeks before Tet, they had attempted to lure allied forces from the coastal lowlands to the mountains by threatening several of the Marine combat bases along Highway 9 in the western part of the province. But while the U.S. Marines had shifted some forces to their base at Khe Sanh, MACV commanders had reinforced eastern Quang Tri Province in late January with the 1st Brigade of the 1st Cavalry Division. The existence of major American units near Quang Tri City came as a shock to the enemy, but with little time to make adjustments, the Communists decided to move forward with their original plan.

ARVN 1st Regiment airfield and compound at La Vang Thuong, fall 1967, looking south

ARVN 1st Regiment airfield and compound at La Vang Thuong, fall 1967, looking south

`

The brunt of the attack would fall on the ARVN forces in and around the city. These were the 1st Vietnamese Regiment, the 9th Airborne Battalion, an Armored Personnel Carrier (APC) Troop attached to the 1st Regiment (2nd Troop of the ARVN 7th Cavalry), the National Police—a paramilitary body led by regular military officers stationed within the city—and Regional and Popular Force (militia) elements in the city. The 1st Regiment had two of its battalions in positions to the north of the city, and one to the northeast, protecting pacified villages in those areas. The Regiment’s fourth battalion was in positions south of the city in and around the regiment’s headquarters at La Vang. One Airborne company was bivouacked in Tri Buu village on the northern edge of the city with elements in the Citadel, and two Airborne companies were positioned just south of the city in the area of a large cemetery where Highway 1 crosses Route 555.

The 1st Brigade of the 1st US Cavalry Division commanded by Colonel Donald V. Rattan had been moved from near Hue and Phu Bai six days earlier to Quang Tri Province, with its headquarters at Landing Zone Betty two kilometers south of Quang Tri City, with the bulk of its force at LZ Sharon, another kilometer south, in order to launch attacks on Communist Base Area 101 roughly 15 kilometers (9.3 mi) to the west-southwest. The brigade had an additional mission to block approaches into the city from the southwest but was primarily focused on its offensive mission. Accordingly, had quickly established two fire bases, one 15 kilometers (9.3 mi) west of the city and another in the middle of the Communist base areas in the hills west of Quang Tri City. The 2nd Brigade of the 101st Airborne Division was also moved into Quang Tri Province in late January, reinforcing the two brigades of the 1st Cavalry in the area.

The coordinated Communist assault was scheduled to begin at 0200 on 31 January. The 10th Sapper began its attacks on time, but the arrival and attacks of the PAVN infantry and artillery units were delayed by at least two hours by heavy rains and swollen streams and their lack of familiarity with the geography of Quang Tri Province, and they did not start to move into position until about 0400. As a result, Regional and Popular Forces, local National Police elements, and elements of the 1st ARVN Regiment located within the city were able to respond to the sappers without having to contend with the main attack at the same time.

As the 814th Battalion was moving into position to attack Quang Tri from the northeast, it unexpectedly encountered the 9th ARVN Airborne company in Tri Buu village, which engaged it in a sharp firefight lasting about 20 minutes. The Airborne company was nearly annihilated and an American adviser killed, but its stubborn resistance stalled the 814th battalion’s assault on the Citadel and the city. By 0420, the heavy communist pressure and overwhelming numbers forced the surviving South Vietnamese paratroopers to pull back into the city, and the 814th attacked and attempted to enter the Citadel unsuccessfully.

The assault against the eastern and southeastern part the city was initially successful. At about 0420, as the 814th Battalion began its delayed assault on the Citadel, the K4 Battalion of the 812th PAVN Regiment skirted the lower edge of Tri Buu Village and swarmed into the city, attempting to seize strong points and assaulting the Citadel from the south. South Vietnamese irregulars and National Policemen slowed the enemy’s advance, however, and it’s assaults on the southern wall of the Citadel were beaten back. Adding to its difficulties was the failure of an expected “general uprising” it had been told to expect. To the south, the PAVN K6 battalion slammed unexpectedly into the two Airborne companies resulting in an intense, extended firefight.

Shortly after dawn the 1st Infantry Regimental commander ordered his battalions to recapture the city. His three battalions north of Quang Tri City began marching toward the capital. Along the way, they collided with the 808th Battalion blocking Highway 1 near the Trieu Phong District headquarters which temporarily stopped their assault. At about the same time, ARVN troops at La Vang began moving north toward the fighting between the Airborne companies and the K6 Battalion in the cemetery south of the city, and were ambushed by the K6th, slowing their advance to a crawl. Fighting south of the city there was heavy throughout the morning. Only the NVA K5 Battalion, holding a position in Hai Lang District to block reinforcements from Hue, remained unengaged in the fighting.

At the start of the communist attack, the ARVN 1st Regimental headquarters at La Vang and Col. Rattan’s headquarters at Landing Zone Betty south of La Vang came under sporadic rocket and mortar attacks and ground assaults by elements of the 10th Sapper Battalion, while extremely heavy fog hampered visibility. The fog also prevented shifting the 1st Battalion of the 8th US Cavalry Regiment (1st Cavalry Division) its base camp in the mountains west of Quang Tri. The 1st Battalion, 502nd Infantry Regiment, of the 101st Airborne Division, which was under the control of the 1st Cavalry Division, continued its base defense mission and just west of Quang Tri.

This left only the 1st Battalion of the 12th US Cavalry Regiment and the 1st Battalion of the 5th Cavalry Regiment to support the ARVN units engaged with the Communist. Both battalions had opened new fire bases to the west of Quang Tri, along the river valley leading to Khe Sanh. At approximately 1345 on 31 January, Col. Rattan directed the battalions to close out the new fire bases and launch assaults as soon as possible to reduce the Communists’ ability to bring additional forces into the city and also blocking their withdrawal. By 1600, the cavalry battalions had air assaulted into five locations northeast, east, and southeast of Quang Tri City where Brewer intelligence sources had showed Communist units located. The American helicopters received heavy fire as they landed troops east of the city in the middle of the heavy weapons support of the K-4 Battalion, and fighting there continued until 1900 as the Communists fought with machine guns, mortars, and recoilless rifles. Engaged by ARVN forces in and near the city, and by American forces on the east, the K4 Battalion was soon overcome.

Two companies of the 1st Battalion of the 5th Cavalry air-assaulted southeast of Quang Tri engaging the K6 Battalion from the rear in a heavy firefight, while ARVN troops blocked and attacked it from the direction of the city. American helicopter gunships and artillery hit the Communist troops hard causing significant further casualties. By nightfall on the 31st, the battered 812th Regiment decided to withdraw, though clashes continued throughout the night.

Quang Tri City was clear of Communist troops by midday on 1 February, and ARVN units with U.S. air support had cleared Tri Buu Village of PAVN troops. The remnants of the 812th, having been hit hard by ARVN defenders and American air power and ground troops on the outskirts of the city, particularly artillery and helicopters, broke up into small groups, sometimes mingling with crowds of fleeing refugees, and began to exfiltrate the area, trying to avoid further contact with Allied forces. They were pursued by the American forces in a circular formation forced contact with the fleeing Communists over the next ten days. Heavy fighting continued with large well-armed Communist forces south of Quang Tri City, and there were lighter contacts in other areas. This pursuit continued throughout the first ten days of February.

The American military considered the Communist attack on Quang Tri “without a doubt one of the major objectives of the Tet offensive”. They attributed the decisive Communist defeat to the hard-nosed South Vietnamese defense, effective intelligence on Communist movements provided by Robert Brewer, and the air mobile tactics of the 1st Cavalry Division. Between 31 January and 6 February, the allies killed an estimated 914 Communists and captured another 86 in and around Quang Tri City.

The rapid defeat of the regimental-size enemy force that assaulted Quang Tri City proved to be one of the most decisive victories the allies secured during the Tet Offensive. Aside from mopping up operations in the countryside, it was effectively over less than twenty-four hours after it had begun. Most elements of the 812th PAVN Regiment were so badly mauled that they avoided all contact for the next several weeks, when they otherwise might have played a role in the battle for Hue 50 kilometers (31 mi) to the south. Losing the province capital would have been a severe blow to South Vietnamese morale, and PAVN units could have caused extensive damage to nearby ARVN and American bases had they captured long range ARVN artillery pieces in the Citadel. They would also have cut off resupply traffic on Highway 1 to allied forces along the DMZ and the Marines at Khe Sanh. The PAVN’s swift defeat preserved an important symbol of South Vietnamese national pride and allowed the allies to devote more resources to other battles in northern I Corps, particularly to the struggle for Hue.

The Battle of Ben Het Special Forces Camp

Ben Het Camp (also known as Ben Het Special Forces Camp, Ben Het Ranger Camp and FSB Ben Het) is a former U.S. Army and Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) base northwest of Kon Tum in the Central Highlands of Vietnam. The camp was notable for being the site of a tank battle between the U.S. Army and the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN), one of the few such encounters during the Vietnam War.

The 5th Special Forces Group Detachment A-244 first established a base at Ben Het in the early 1960s to monitor communist infiltration along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The base was located approximately 13 km from the Vietnam-Laos-Cambodia tri-border area, 15 km northwest of Đắk Tô and 53 km northwest of Kon Tum.

On 3 March 1969, Ben Het was attacked by the PAVN 66th Regiment, supported by armored vehicles of the 4th Battalion, 202nd Armored Regiment. One of the attacking PT-76s detonated a land mine, which alerted the camp and lit up the other PT-76s attacking the base. Flares were sent up, exposing adversary tanks, but sighting in on muzzle flashes, one PT-76 scored a direct hit on the turret of an M-48 of the 1st Battalion, 69th Armor Regiment, killing two crewmen and wounding two more. Another M-48, using the same technique, destroyed a PT-76 with their second shot. At daybreak, the battlefield revealed the wreckage of two PT-76s and one BTR-50 armored personnel carrier.

The PAVN 28th and 66th Regiments continued to besiege the base from May to June 1969.

Since January 1972 it had become clear that the North Vietnamese were building up for offensive operations in the tri-border region. ARVN forces had been deployed forward toward the border in order to slow the PAVN advance and allow the application of airpower to deplete North Vietnamese manpower and logistics. To counter the possible threat from the west, two regiments of the 22nd Division were deployed to Tân Cảnh and Đắk Tô and the 1st Squadron, 19th Armored Cavalry Regiment equipped with M41 tanks was deployed to Ben Het. On 24 April, the 2nd PAVN Division, elements of the 203rd Tank Regiment, and several independent regiments of the B-3 Front attacked Tân Cảnh and Đắk Tô rapidly overrunning both bases with their T-54 tanks. On 9 May 1972, elements of the PAVN 203rd Armored Regiment assaulted Ben Het. ARVN Rangers destroyed the first three PT-76 tanks with BGM-71 TOW missiles, thereby breaking up the attack. The Rangers spent the rest of the day stabilizing the perimeter ultimately destroying 11 tanks and killing over 100 PAVN.

My friend, Frank Evans participated in this battle and wrote a book about it (Stand To…A Journey to Manhood) which can be found on Amazon. Here is an excerpt about the battle:

Ben Het was under siege. Each day, a deadly flurry of artillery and mortar rounds destroyed bunkers and damaged equipment. Casualties increased. Small-scale ground attacks tested the defenses of the camp. Friendly patrols near the camp encountered enemy soldiers in groups of five to ten men daily. Frequently, larger enemy units operated near the camp. On a recent mission, a mobile strike force unit reported battling an entrenched battalion-sized force of at least two hundred. Convoys were ambushed regularly. Aircraft received ground fire at every attempt to land. Helicopters, and occasionally a C-130 or C-7A, dared to brave the machinegun and mortar fires on the airstrip to bring in supplies. Our radio communication with the tactical command post in Dak To kept them informed about how defenses were holding up here.

I began to appreciate the comparison that Sergeant Spence made between the French garrison at Dien Bien Phu and Ben Het. Morale was high in spite of the constant barrage of enemy fires. Internal exchanges also relied upon radio, the least secure means of communication since the enemy could easily intercept them with a radio and the right frequency. We had to assume our conversations were being monitored; intermittently, an unknown radio station attempted to obtain friendly information on the location of patrols and their activities. The more secure field telephone landline wire was repeatedly cut by the constant bombardment or by saboteurs.

Sergeant Smith picked up the radio log and asked, “Anything goin’ on this morning, sir?”

“We had one CIDG KIA on the west hill last night. One of the MSF units lost two KIA and two WIA, plus two US WIA. One was pretty badly wounded. They ran into bad guys in bunkers and took heavy automatic weapons fire. They’re still in contact. The enemy has claymore mines, too.”

“Uh huh. Must’ve captured some of our claymores somewhere. I tell you, sir. The enemy’s moving all over the place around here. They’re gettin’ bolder.”

“We have two MSF companies reinforcing us plus the one here in the camp. Another one has been requested from Dak Pek to reinforce the MSF company in contact now. Spooky has been working the hills and trail networks.”

“I heard it. Three Gatling guns. Man, six thousand rounds per minute each! Sorta sounds like hmmmmmmmm…hmmmmmmmm…hmmmmmmmm. Those guns are spewing out red tracers every fifth round, but it looks like a steady stream of red lines from the aircraft to the ground. No wonder Charlie is afraid of the Dragon. Thank you for the excerpt Frank and Thank you for your service!

Here too, is a YouTube video also describing the battle:

The Battle of Binh Ghia

The Battle of Binh Gia (Vietnamese: Trận Bình Giã), which was part of a larger communist campaign, was conducted by the Viet Cong from December 28, 1964, to January 1, 1965, during the Vietnam War in Bình Giã. The battle took place in Phước Tuy Province (now part of Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu Province), South Vietnam.

The year of 1964 marked a decisive turning point in the Vietnam War. The fragility of the South Vietnamese government was reflected on the battlefield, where its military experienced great setbacks against the Viet Cong. Taking advantage of Saigon’s political instability, Communist leaders in Hanoi began preparing for war. Even though key members of North Vietnam’s Politburo disagreed on the best strategy to reunite their country, they ultimately went ahead to prepare for armed struggle against South Vietnam and their American supporters.

Towards the end of 1964, the Viet Cong commenced a series of large-scale military operations against the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN), as ordered by the North Vietnamese government. As part of their Winter-Spring Offensive, the Viet Cong unleashed its newly created 9th Division against the South Vietnamese forces at Bình Giã, fighting a large set-piece battle for the first time. Over a period of four days, the Viet Cong 9th Division held its ground and mauled the best units the South Vietnamese army could send against them, only breaking after intense attack by U.S. bombers.

In July 1964, the Viet Cong 271st and 272nd Regiments, began moving into the provinces of Bình Dương, Bình Long and Phước Long to carry out their mission. During the first phase of their campaign, the Viet Cong regiments overran several strategic hamlets at Xan Sang, Cam Xe, Dong Xa, and Thai Khai. Between August and September 1964, Viet Cong regiments executed deep thrusts into Bình Dương and Châu Thành to apply additional pressure on South Vietnamese outposts situated on Route 14. During the second phase of their campaign, the Viet Cong ambushed two South Vietnamese infantry companies and destroyed five armored vehicles, which consisted of M24 Chaffee light tanks and M113 armored personnel carriers. The Viet Cong defeated regular ARVN units at the strategic hamlets of Bình Mỹ and Bình Co.

During the war about 6,000 people lived in Bình Giã, and most of whom were staunchly anti-communist. The inhabitants of Bình Giã were Roman Catholic refugees who had fled from North Vietnam in 1954 during Operation Passage to Freedom because of fears of Communist persecution. To prepare for their main battle, the Viet Cong 272nd Regiment was ordered to block Inter-provincial Road No. 2 and 15, and destroy any South Vietnamese units attempting to reach Bình Giã from the south-western flank of the battlefield. In the days leading up to the battle, the Viet Cong often came out to harass the local militia forces. On December 9, 1964, the 272nd Regiment destroyed an entire South Vietnamese mechanized rifle company along Inter-provincial Road No. 2, destroying 16 M-113 APCs. On December 17, the 272nd Regiment destroyed another six armored vehicles on Inter-provincial Road No. 15.

During the early hours of December 28, 1964, elements of the Viet Cong 271st Regiment and the 445th Company, signaled their main attack on Bình Giã by penetrating the village’s eastern perimeter. There, they clashed with members of the South Vietnamese Popular Force militiamen, which numbered about 65 personnel. The militia fighters proved no match for the Viet Cong and their overwhelming firepower, so they quickly retreated into underground bunkers, and called for help. Once the village was captured, Colonel Ta Minh Kham, the Viet Cong regimental commander, established his command post in the main village church and waited for fresh reinforcements, which came in the form of heavy mortars, machine guns and recoilless rifles. To counter South Vietnamese helicopter assaults, Colonel Kham’s troops set up a network of defensive fortifications around the village, with trenches and bunkers protected by land mines and barbed wire. The local Catholic priest, who was also the village chief, sent a bicycle messenger out to the Bà Rịa district headquarters to ask for a relief force. In response, the Bà Rịa district chief sent out elements of two Vietnamese Rangers battalions to retake Bình Giã. On December 29, two companies of the ARVN 33rd Ranger Battalion and a company from the 30th Ranger Battalion were airlifted into area located west of Bình Giã, by helicopters from the U.S. 118th Aviation Company to face an enemy force of unknown size.

However, as soon as the soldiers from the 30th and 33rd Ranger Battalions arrived at the landing zone, they were quickly overwhelmed by the Viet Cong in a deadly ambush. The entire 30th Ranger Battalion was then committed to join the attack, but they too did not initially succeed in penetrating the strong Viet Cong defensive lines. Several more companies of the Rangers then arrived for an attack from multiple directions. Two companies of the 33rd Ranger Battalion advanced from the northeast. One of them came to the outskirts of the village, but was unable to break through the enemy defenses. The other one, trying to outflank the enemy, had been lured into a kill zone in open terrain and were quickly obliterated in an ambush by the three VC battalions using heavy weapons. The two companies suffered a 70 percent casualty rate, and survivors were forced to retreat to the nearby Catholic church. The 30th Rangers had more success by assaulting from the western direction and succeeded in fighting their way into the village, aided by local residents. It however also suffered heavy losses, with the battalion commander and his American adviser severely wounded. The local civilians in Bình Giã retrieved weapons and ammunition from the dead Rangers, and hid the wounded government soldiers from the Viet Cong. The 38th Ranger Battalion, on the other hand, landed on the battlefield unopposed by the Viet Cong, and they immediately advanced on Bình Giã from the south. Soldiers from the 38th Rangers spent the whole day fighting, but they could not break through their enemies’ defenses to link up with the survivors hiding in the church, and fell back after calling in mortar fire to decimate Viet Cong fighters moving to encircle them.

The morning of December 30, the 4th South Vietnamese Marine Battalion moved out to Biên Hòa Air Base, waiting to be airlifted into the battlefield. The 1/4th Marine Battalion was the first unit to arrive on the outskirts of Bình Giã, but the 1st Company commander decided to secure the landing zone, to wait for the rest of the battalion to arrive instead of moving on to their objective. After the rest of the 4th Marine Battalion had arrived, they marched towards the Catholic church to relieve the besieged Rangers. About one and a half hours later, the 4th Marine Battalion linked up with the 30th, 33rd and 38th Ranger Battalions, as the Viet Cong began withdrawing to the northeast. That afternoon the 4th Marine Battalion recaptured the village, but the Viet Cong was nowhere to be seen, as all their units had withdrawn from the village during the previous night, linking with other Viet Cong elements in the forest to attack the government relief forces. On the evening of December 30, the Viet Cong returned to Bình Giã and attacked from the south-eastern perimeter of the village. The local villagers, who discovered the approaching Viet Cong, immediately sounded the alarm to alert the ARVN soldiers defending the village. The South Vietnamese were able to repel the Viet Cong, with support from U.S. Army helicopter gunships flown out from Vung Tau airbase.

While pursuing the Viet Cong, a helicopter gunship from the U.S. 68th Assault Helicopter Company was shot down and crashed in the Quảng Giao rubber plantation, about four kilometers away from Bình Giã, killing four of its crewmen. On December 31, the U.S. Marines Advisory Group sent a team of four personnel, led by Captain Donald G. Cook, to Bình Giã to observe conditions on the battlefield. At the same time, the 4th Marine Battalion was ordered to locate the crashed helicopter and recover the bodies of the dead American crewmen. Acting against the advice of his American advisor, Major Nguyễn Văn Nho, commander of the 4th Marine Battalion, sent his 2/4th Marine Battalion company out to the Quảng Giao rubber plantation. Unknown to the 4th Marine Battalion, the Viet Cong 271st Regiment had assembled in the plantation. About one hour after they had departed from the village of Bình Giã, the commander of the 2/4th Marine Battalion reported via radio that his troops had found the helicopter wreckage and bodies of four American crewmen. Shortly afterward, the Viet Cong opened fire and the 2/4th Marine Battalion was forced to pull back. In an attempt to save the 2nd Company, the entire 4th Marine Battalion was sent out to confront the Viet Cong. As the lead element of the 4th Marine Battalion closed in on the Quảng Giao plantation, they were hit by accurate Viet Cong artillery fire, which was soon followed by repeated human wave attacks. Having absorbed heavy casualties from the Viet Cong’s ambush, the 2/4th Marine Battalion had to fight their way out of the plantation with their bayonets fixed. During the entire ordeal, the company did not receive artillery support because the plantation was beyond the range of 105mm artillery guns based in Phước Tuy and Bà Rịa. They, however, escaped with the crucial support of the U.S. aircraft and helicopters whose rocket attacks forced the enemy to pull back and halted their attempt at pursuit.

In the morning of December 31, the 4th Marine Battalion returned to the crash site with the entire force and the American graves were located and their corpses were dug up. At about 3 pm, a single U.S. helicopter arrived on the battlefield to evacuate the casualties, but they only picked up the bodies of the four American crewmen, while South Vietnamese casualties were forced to wait for another helicopter to arrive. At 4 pm, Major Nguyễn Văn Nho ordered the 4th Marine Battalion to carry their casualties back to the village, instead of continuing to wait for the helicopters. As the 4th Marine Battalion began their return march, three Viet Cong battalions, with artillery support, suddenly attacked them from three directions. The battalion’s commanding and executive officers were immediately killed and air support was not available. Two Marine companies managed to fight their way out of the ambush and back to Bình Giã, but the third was overrun and almost completely wiped out. The fourth company desperately held out at a hilltop against Viet Cong artillery barrages and large infantry charges, before slipping out through the enemy positions at dawn. The 4th Marine Battalion of 426 men lost a total of 117 soldiers killed, 71 wounded and 13 missing. Among the casualties were 35 officers of the 4th Marine Battalion killed in action, and the four American advisers attached to the unit were also wounded. Backed by U.S. Air Force bombers, on January 1 three battalions of ARVN Airborne reinforcements arrived, they were too late as most of the Viet Cong had already withdrawn from the battlefield.

The battle of Bình Giã reflected the Viet Cong’s growing military strength and influence, especially in the Mekong Delta region. It was the first time the Viet Cong launched a large-scale operation, holding its ground and fighting for four days against government troops equipped with armor, artillery, and helicopters, and aided by U.S. air support and military advisers. The Viet Cong demonstrated that when well-supplied with military supplies from North Vietnam, they had the ability to fight and inflict damage even on the best ARVN units.

The Viet Cong apparently suffered light casualties with only 32 soldiers officially confirmed killed, and they did not leave a single casualty on the battlefield. In recognition of the 271st Regiment’s performance during the Bình Giã campaign, the NLF High Command bestowed the title ‘Bình Giã Regiment’ on the unit to honor their achievement.

Unlike their adversaries, the South Vietnamese military suffered heavily in their attempts to recapture the village of Bình Giã and secure the surrounding areas. The South Vietnamese and their American allies lost the total of about 201 personnel killed in action, 192 wounded and 68 missing. In just four days of fighting, two of South Vietnam’s elite Ranger companies were destroyed and several others suffered heavy losses, while the 4th Marine Battalion was rendered ineffective as a fighting force. At that stage of the war, Bình Giã was the worst defeat experienced by the South Vietnamese. Despite their losses, the South Vietnamese army considered the battle as their victory and erected a monument at the site of the battle to acknowledge the sacrifices of the soldiers who had fallen to retake Bình Giã.

The Hill Fights

The Hill Fights (also known as the First Battle of Khe Sanh) was a battle during the Vietnam War between the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) 325C Division and United States Marines in spring of 1967.

On 20 April operational control of the Khe Sanh area passed to the 3rd Marine Regiment.

On 22 April 1967 SLF Bravo comprising 2nd Battalion 3rd Marines supported by HMM-164 had commenced Operation Beacon Star on the southern part of the Street Without Joy straddling Quảng Trị and Thừa Thiên Provinces against the Vietcong 6th Regiment and 810th and 812th Battalions.

Hill 861

On 24 April 2nd Platoon, Company B, 3rd Battalion 3rd Marines moved to Hill 700 to establish a mortar position to support another Company. 5 Marines then moved to Hill 861 to establish an observation post, but as they entered a bamboo grove near the summit they were ambushed by the PAVN killing 4 Marines.

After this contact, a squad was sent to investigate and rescued the lone survivor of the ambush, as they attempted to recover the bodies of the dead they were met with fire and withdrew into the mortar position. Another squad moved to the ambush site and recovered two bodies but as an evacuation helicopter approached the hilltop it was hit by heavy fire, which was suppressed by helicopter gunships.

1st and 3rd Platoons Company B were then ordered to move southeast across Hill 861 to cut off the PAVN but were hit by mortar fire, medevac helicopters were called in, attracting PAVN fire each time. 1st and 3rd Platoons dug in for the night while 2nd Platoon withdrew to Khe Sanh Combat Base (KSCB). Marines losses for the day were 12 dead, 2 missing (later found dead) and 17 wounded.

The next morning Company B continued its slow advance on Hill 861, hampered by fog, difficult terrain and PAVN fire. On the afternoon of 25 April, Company K, 3rd Marines (which was scheduled to relieve Company B at KSCB from 29 April) arrived at KSCB and immediately moved towards Hill 861 to support Company B. 1st and 3rd Platoons Company K moved up Hill 861 on different approaches and 1st Platoon was hit by fire from well-entrenched PAVN 300m from the summit. 2nd Platoon was sent to reinforce 1st Platoon and the fighting continued until nightfall when the Marines dug in. At 18:00 Company K, 9th Marines was flown into KSCB to support the attack.

At 05:00 on 26 April the 3rd Battalion command post and KSCB were hit by mortar and recoilless rifle fire. Company K continued their assault on Hill 861 and was joined by Company K, 9th Marines around midday. The assault made little progress and the Marines withdrew protected by fire from helicopter gunships. Company B was also heavily engaged throughout the morning eventually breaking contact at 12:00 and establishing a defensive perimeter on a knoll, medevac helicopters were called in but as they approached this brought PAVN mortar fire and by 14:45 the Company commander reported that he was unable to move. Artillery was then walked into and around the Company’s position forcing the PAVN to fall back, a Marine platoon was then sent to assist Company B as it fell back to the Battalion command post.

On 27 April 3/3 Marines returned to KSCB for replacements and Battery B 12th Marines arrived at KSCB to support Battery F. Marine artillery and aircraft were used to pound Hill 861 throughout the 27th and 28th, dropping 518,700 pounds of bombs and 1800 artillery round on the hill. Due to the dense foliage and overhead cover protecting many of the bunkers Marine aircraft dropped Snakeye bombs to remove the foliage and expose the bunkers and then larger bombs (up to 2000 lb) to destroy them.

The Marines’ plan was for 2/3 Marines to take Hill 861, then 3/3 Marines would move west securing the ground between Hill 861 and Hill 881 South. 2/3 Marines would then provide flank security for 3/3 Marines and take Hill 881 North.

On the afternoon of 28 April 2/3 Marines moved up Hill 861 with minimal opposition as the PAVN had withdrawn from the Hill. The Marines found 25 bunkers and numerous fighting positions and reported an odor of dead bodies across the hilltop.

Hill 881 South

On 29 April with 2/3 Marines having secured Hill 861, 3/3 Marines advanced from KSCB towards a hill 750m northeast of Hill 881S that was to be used as an intermediate position for the attack on Hill 881S. Company M, 9th Marines engaged a PAVN platoon, while Company M 3rd Marines secured the intermediate position and dug in.

On 30 April 2/3 Marines moved from Hill 861 to support 3/3 Marines and walked into a PAVN bunker complex suffering 9 killed and 43 wounded, the Marines backed off to let artillery and air support hit the bunkers and then overran them. Company M 3rd Marines and Company K 9th Marines began their assault on Hill 881S encountering minimal resistance until 10:25 when they were hit by mortar fire and then heavy fire from numerous PAVN bunkers. The Marines were pinned down and only able to disengage after several hours with gunship and air support, the Marines suffered 43 killed and 109 wounded in the engagement while PAVN losses were 163 killed. Company M 3rd Marines was rendered combat ineffective and was replaced by Company F 2/3 Marines and Company E, 9th Marines was deployed to KSCB on the afternoon of 1 May.

The Marines withdrew from Hill 881S to allow for an intense air bombardment, on 1 May 166 Marine sorties were flown against Hills 881 North and South and over 650,000 lbs of bombs were dropped on them resulting in over 140 PAVN killed.

On 2 May Companies K and M, 9th Marines assaulted Hill 881S capturing it with minimal resistance by 14:20. The Marines discovered over 250 bunkers protected by anywhere between 2 and 8 layers of logs and then 4–5 ft of earth, only 50 bunkers remained intact after the bombing.

Hill 881 North

At 10:15 on 2 May Companies E and G 2/3 Marines assaulted Hill 881N from the south and east. Company G encountered a PAVN position and pulled back to allow for artillery support. Company E almost reached the summit of the hill when it was hit by an intense rainstorm and the Battalion was pulled back into night defensive positions.

At 04:15 on 3 May a PAVN force attacked Company E’s night defensive position, penetrating the east of the position and reoccupying some bunkers. A Marine squad sent to drive out the PAVN was hit by machine gun fire and a scratch squad of engineers was sent to support them while air and artillery strikes were called in on the PAVN. A flareship arrived overhead and the Marines on Hill 881S could see approximately 200 PAVN forming up to attack Company E from the west and fired over 100 rounds of recoilless rifle fire to break up this fresh assault. At dawn, reinforcements were flown in to support Company E while Company H 2/3 Marines attacked the PAVN from the rear. The last bunker was cleared at 15:00, 27 Marines were killed and 84 wounded in the attack, while the PAVN had lost 137 killed and 3 captured. Prisoner interrogations revealed plans for another attack on the Marine positions that night but this did not occur.

At 08:50 on 5 May Companies E and F 2/3 Marines began their assault on Hill 881N, PAVN fire increased as they neared the summit and both Companies pulled back to allow for air and artillery strikes. The assault resumed at 13:00 and by 14:45 the hilltop had been captured.

After securing Hill 881N the Marines thoroughly searched the area around Hills 881N and 881S and air and artillery strikes were called in on suspected PAVN positions, but it appeared that the PAVN had withdrawn north across the DMZ or west into Laos.

Hill 861 in the forefront and beyond are 881S (left peak) and 881N

Hill 861 in the forefront and beyond are 881S (left peak) and 881N

On 9 May Company F 2/3 Marines encountered a PAVN force 3.2 km northwest of Hill 881N, artillery fire was called in and Company E was deployed in support. The engagement resulted in 24 Marines killed and 19 wounded while PAVN losses were 31 killed, while a further 203 recent graves were discovered in the area.

At midnight on 9/10 May the PAVN attacked Reconnaissance Team Breaker of the 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion, the PAVN could have easily overrun the Marines but instead targeted the Marine helicopters attempting to extract them severely damaging several helicopters. Marine losses were 4 Reconnaissance Team members and 1 helicopter pilot, while PAVN losses were 7 dead.

The Hill Fights officially ended on 10 May. Marine losses were 155 dead and 425 wounded while PAVN losses were 940 confirmed dead. Intelligence gathered after the battle was over found that the PAVN plan was to build up stores and positions north of KSCB, isolate the base from resupply by attacks on Marines bases in northern I Corps, launch a diversionary attack on Lang Vei Special Forces Camp (which occurred as scheduled on 4 May) and then several Regiments of the 325C Division would overrun KSCB, however, the encounter on 24 April had frustrated the PAVN plan.

The Battle of Trang Bang

1ST BDE – A combined arms team of 25th Inf Div armor and infantry killed more than 100 Viet Cong and North Vietnamese forces in a third full day of heavy fighting 54 kms northwest of Saigon. The actions brought to 340 the total number of enemy dead since elements of the 2nd Bde 27 Inf. Wolfhounds of the 25th Division came in contact with an estimated enemy regiment in rice paddies and hedgerows near the district capital of Trang Bang.

The action began as Co B, 2nd Bn, 14th Inf, touched down in open fields east of a small village four kms west of the scene of a 20-hour battle that cost enemy forces 87 dead. Repeating the first fight, the company came under heavy enemy small arms, automatic weapons and rocket fire as it approached the village. Calling for reinforcements, two more companies joined the battle. They also began to return fire with small arms, machine guns and grenade launchers against the entrenched enemy.

Soon after the contact began helicopter gunships, artillery and Air Force fighter bombers were called in to aid the embattled battalion. In addition, a nearby armor task force, led by the 2nd Bn, 34th Armor, with Co C of the 1st Bn (Mech), 5th Inf, sped to the scene of the fight to block off the village to the south. Repeated assaults by the U.S. forces were stopped by the enemy. At nightfall, the infantry-armor task force pulled back while 20 air strikes and 5000 rounds of artillery pounded the area throughout the night.

An early morning assault again halted when the ground units received heavy fire upon approaching the village. After the second series of artillery and air strikes, the U.S. forces encountered only light resistance and swept through the village. According to LTC Alfred M. Bracy, task force commander, an estimated Viet Cong and North Vietnamese battalion had occupied the village. Bracy praised his men for their actions, stating that their morale was high despite the two around-the-clock battles in three days. “There’s a job to do and we will do it,” said Bracy of his unit’s spirit.

SP4 Jimmy J. Mathis of Cochran, Ga., repeated his commander’s comments, “We’ve had so much contact lately, doing the right thing is just becoming natural in a fight.” A few of the men even expressed a certain sympathy for the enemy. “When I get tired and worn out, I think about how much better off we are than Charlie, and I feel better,” said SP4 Daniel R. Mitchell of Santa Maria, Calif., as he watched an air strike fall on the enemy. Captured enemy equipment in the action included 14 AK-47 assault rifles, 2 RPG-2 rocket launchers, 6 Chicom light machine guns and thousands of rounds of small arms ammunition.

This is also the same village made infamous in 1972 when a South Vietnamese Air Force pilot mistakenly dropped napalm on the village. A photo taken shows a young girl who was severely burned and running up the street toward troops (Napalm girl).

VC MACHINE GUN– A captured Viet Cong heavy anti-aircraft machine gun receives close inspection by members of the 2nd Bn, 34th Armor, 25th Inf Div, who captured it in a battle 54 kms northwest of Saigon. (Photo By SP5 Gary Johnson)

Battle of Tam Quan

The following account is told by Rigo Ordaz who participated in the battle and published this article on History dot com. The Battle of Tam Quan Dec. 6-20 pitted elements of the Ist Cavalry Division’s First Brigade and the First Battalion (Mechanized) 50th Infantry against a tenacious and well-fortified enemy of the 22nd NVA Regiment of the 3rd (Sao Vang-Yellow Star) NVA Division. The battle took place close to the town of Tam Quan in the Central Highland’s coastal northern part of Binh Din Province. The Battle of Tam Quan was the biggest and most successful during Operation Pershing. The victorious U.S. units destroyed at least two battalions of the 22nd NVA Regiment which was setting up for the upcoming 1968 Tet Offensive. It accounted for 1/8 of all enemy killed for the whole year. When the smoke of the battle cleared the 1st Cavalry Division and the 1st Battalion (Mechanized), 50th Infantry emerged victorious and the enemy lost over 650 of their troops against only 58 U.S casualties in a battle which is rated 15th of the 20 deadliest battles of the Vietnam War. Unfortunately, the 1/50(M) Infantry lost 12 Americans on the 10th of December alone.

Aerial reconnaissance forces of the 1st Cavalry Divisions had found many indications of a troop buildup which includes an enormous Russian Ship to Shore radio on the beach. During the month of November and the first part of December 1967 there were many indications that the enemy was building up forces in preparation for the coming Tet Offensive in the Bong Son plains of Binh Din Province. Their major targets would be U.S. and ARVN forces and the major district capitals.

On the 6th day of December a reconnaissance helicopter of the 1/9th , 1st Cavalry Division spotted a radio antenna sticking out of a hooch in the vicinity of the village of Dai Dong . Troop A 1/9th sent a platoon of the Blues (Infantry) to investigate. At 1630 Hours while approaching the area the platoon came under intense automatic and small arms fire and was pinned down. The Weapons Platoon of the 1/9 was sent in to help and they also were pinned down and unable to move. They had stumbled upon a large enemy force of the 22nd NVA Regiment. This was the beginning of the Battle of Tam Quan.

The two platoons were in great danger of being overrun and destroyed. It was late in the afternoon and soon it would be night time. At 1725 the 1st Bde assumed control of the action from the 2nd Bde and directed B Co. 1/8 Cav to the contact area and joined up with a platoon of the A Co. 1/50(Mech) Infantry which had been dispatched from LZ English a few miles away. The combined troops encountered stiff resistance from a well-entrenched enemy. With the firepower of the platoon of APCs they were finally able to extract the two platoons of 1/9th by 2100 Hrs. There is no doubt that had it not been for the firepower of the APCs of A Co. 1/50 (Mech) Infantry, the mission would have been more perilous and at a greater cost of American lives. A 1/50 and B 1/8th Cav established their night perimeter and called in artillery and illumination for the night. They had no further contact that night.

The flamethrower tracks (Zippo) of the 1/50 Mech were especially useful in neutralizing the bunkers and trenches since the 1st Cav Div. had no tanks attached to them at the time. Two D-7 bulldozers from the 19th Engineers were brought in to destroy the bunkers and to clear a pathway for 1/50 APCs. The Engineers had several KIAs from their unit and were credited with killing 10 NVA soldiers. Delta Company 1/50 (Mech) was released from the 2nd Bde and became OPCON to 1/8 Cav, First Bde at 1230 Hrs on 7 December. At 1406 hrs, A,& B 1/8 Cav and Delta Co. 1/50 Mech with flame thrower APCs successfully penetrated the initial bunker and trench network. Delta Company formed all of its APCs in a line facing east with troops of the 1/8 Cav in between the tracks. With all of the company’s 50 Cal. and M60s , M79s and personal weapons going on at the same time, it was beautiful sights and sounds. One of the 1/8 Cav troopers later mentioned that they had never heard so much racket in their life. The enemy probably thought the same thing.

Delta Co. 1/50 Mech and 1/8th Cav had succeeded in penetrating the initial bunker and trench network on the first day U.S. troops counter-attacked. Soon we started seeing some of the enemy coming out of the bunkers some with arms missing, not a sign of pain on their faces. They must have been doped up and some of them still continued firing. Every evening when we pulled to a defensive position for the night we would get replenished with ammunition, food, and hopefully some letters from home.